Imposter Syndrome

The human mind has a tendency to hyper-focus on negatives, especially in regards to ourselves, our identities, and our achievements. When we get 90s on exams, we love to agonize over the ten points we missed instead of rejoicing over demonstrating mastery over nine-tenths—a huge fraction, all things considered—of the material. We’d much prefer to overanalyze awkward interactions we’ve had with others rather than appreciating our ability to put ourselves out there socially in the first place.

These self-critical tendencies are what drive growth and progress; they’re not all that terrible, but they’re definitely not doing our mental health any favors. They’re what drive self-doubt, undervaluation of our abilities, and imposter syndrome, a condition that goes hand-in-hand with being a student at an institution as prestigious at Michigan.

I’ve fallen victim to imposter syndrome far too many times. It’s gotten so extreme that at times, I’ve felt like an imposter for even claiming to suffer from imposter syndrome, as if my personal interpretation of the condition didn’t align with its actual definition. For the longest time, I was convinced that my successes in life—including earning my current place at Michigan—came about not by my own merit, but because I’d somehow “BSed” my way into achieving them. Deep down, I know this is ridiculous. I perceive everyone around me as competent, so why shouldn’t I feel the same way about myself? After all, we all ended up here, didn’t we?

Image by Marvin Meyer on Unsplash

What fascinates me is that despite the fact that those who suffer from imposter syndrome feel like the only imposter in a room full of competent, talented individuals, imposter syndrome itself is more or less universal. So many students on campus feel like they’re somehow faking their credentials while being blissfully unaware of how prevalent, and thereby invalid, this underlying belief actually is. Feeling inferior is so commonplace that it isn’t an indicator of inferiority at all.

This sentiment is pretty hard to remember when I’m in lecture and my professor’s covering topics so confusing that she might as well be speaking a different language, but when I remind myself that everyone around me is likely just as confused as I am, I focus a little less on how “stupid” I must be and a little more on what the hell the professor is actually talking about.

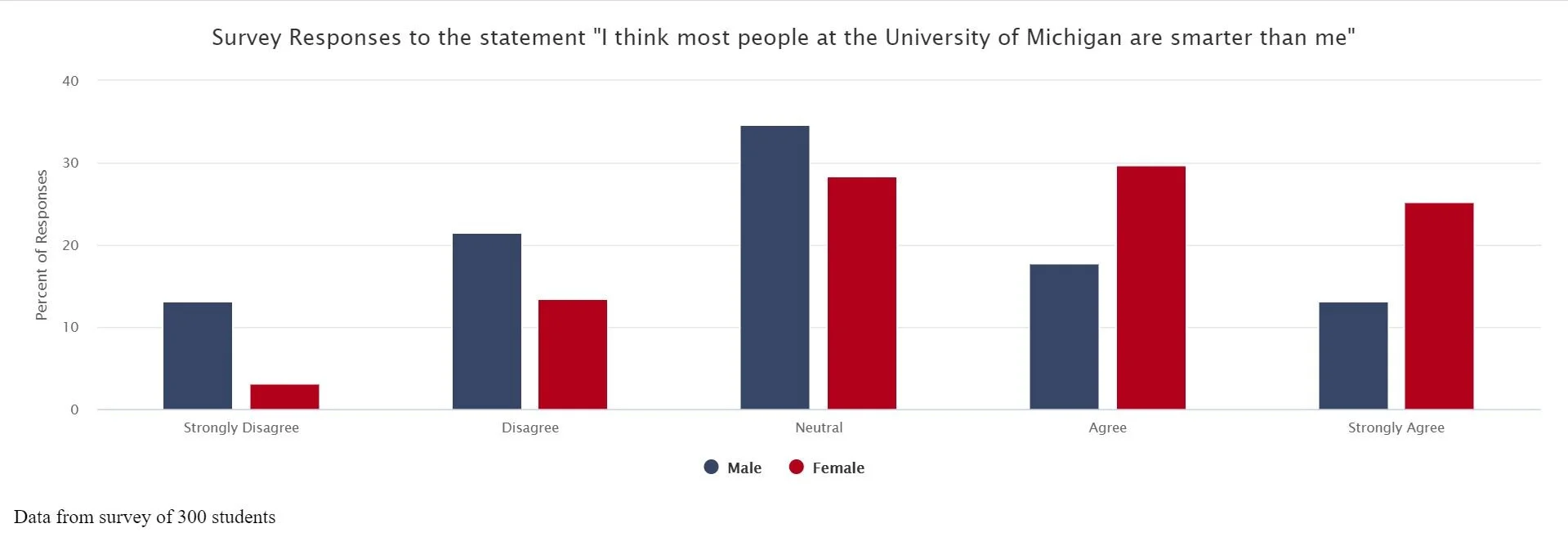

Data from CAPS at the University of Michigan

Interestingly, according to a survey conducted by CAPS, women are more prone to assuming they’re on the lower end of the intelligence scale than men are. Both gender groups were asked to respond to the statement “I think most people at the University of Michigan are smarter than me.” Data from a sample size of 300 students revealed that women were about twice as likely to agree (or strongly agree) with this statement than men, whereas men were twice as likely to disagree. Even when gender is taken out of the equation, the majority of students at Michigan generally feel inadequate compared to their peers.

As Dr. Christine Asiado of CAPS, the conductor of this study, stated in the Michigan Daily, “Thinking about the motto of the university: leaders and best. Does that mean everyone can be a leader and everyone can be the best?” Comparing ourselves to others is natural and pretty inevitable, but when this practice is left unchecked, we come to perceive others’ successes as our own personal failures. People at Michigan regularly experience successes and wins (it’s Michigan, after all), so constantly engaging in this behavior is an easy way to drive ourselves to work to the point of mental exhaustion.

Instead of basing our self-worth on edging out our peers in terms of competition, we need to establish our own metrics for valuing ourselves independent of what others are doing with their lives. This is much easier said than done, as a lot of us are directly competing with other students for the same jobs, grad school seats, and opportunities in general, but separating our efforts from their outcomes is an important step to mitigating imposter syndrome.

As cheesy as it sounds, we need to learn to seek fulfillment from simply having poured our efforts into a task or goal instead of basing our self-worth on whether that goal comes to fruition. Most importantly, we need to squander the inherent negativity that pollutes our headspaces—when we stop illogically attributing our failures to personal incompetency and our successes to dumb luck, we’ll come one step closer to recognizing our strengths instead of brushing them off. On the flip side of this, we’ll treat our shortcomings as obstacles that can be acknowledged and overcome rather than fixed parts of our identity.

Imposter syndrome is a symptom of an underlying issue with the way we approach and interpret goals, successes, and failures. If we redefine success to become progress- and growth-based rather than something that’s contingent on results and beating our peers, we’ll feel more fulfilled, feel less like frauds, build a more supportive community, and perhaps be more personally productive.